RELATION OF FRONTS TO CYCLONES

There is a systemic relationship between cyclones

and fronts, in that the cyclones are usually associated

with waves along fronts—primarily cold fronts.

Cyclones come into being or intensify because pressure

falls more rapidly at one point than it does in the

surrounding area. Cyclogenesis can occur anywhere,

but in middle and high latitudes, it is most likely to

occur on a frontal trough. When a cyclone (or simply

low) develops on a front, the cyclogenesis begins at the

surface and develops gradually upward as the cyclone

deepens. The reverse also occurs; closed circulations

aloft sometime work their way downward until they

appear on the surface chart. These cyclones rarely

contain fronts and are quasi-stationary or drift slowly

westward and/or equatorward.

Every front, however, is associated with a cyclone.

Fronts move with the counterclockwise flow associated

with Northern Hemisphere cyclones and clockwise

with the flow of Southern Hemisphere cyclones. The

middle latitudes are regions where cold and warm air

masses continually interact with each other. This

interaction coincides with the location of the polar

front.

When the polar front moves southward, it is usually

associated with the development and movement of

cyclones and with outbreaks of cold polar air. The

cyclonic circulation associated with the polar front

tends to bring polar air southward and warm moist

tropical air northward.

During the winter months, the warm airflow

usually occurs over water and the cold air moves

southward over continental areas. In summer the

situation is reversed. Large cyclones that form on the

polar front are usually followed by smaller cyclones

and are referred to as families. These smaller cyclones

tend to carry the front farther southward. In an ideal

situation these cyclones come in succession, causing

the front (in the Northern Hemisphere) to lie in a

southwest to northeast direction.

Every moving cyclone usually has two significant

lines

of

convergence

distinguished

by

thermal

properties. The discontinuity line on the forward side of

the cyclone where warm air replaces cold air is the

warm front; the discontinuity line in the rear portion of

the cyclone where cold air displaces warm air is the

cold front.

The polar front is subject to cyclonic development

along it. When wind, temperature, pressure, and upper

level influences are right, waves form along the polar

front. Wave cyclones normally progress along the polar

front with an eastward component at an average rate of

25 to 30 knots, although 50 knots is not impossible,

especially in the case of stable waves. These waves may

ultimately

develop

into

full-blown

low-pressure

systems with gale force winds. The development of a

significant cyclone along the polar front depends on

whether the initial wave is stable or unstable. Wave

formation is more likely to occur on slowly moving or

stationary fronts like the polar front than on rapidly

moving fronts. Certain areas are preferred localities for

wave cyclogenesis. The Rockies, the Ozarks, and the

Appalachians are examples in North America.

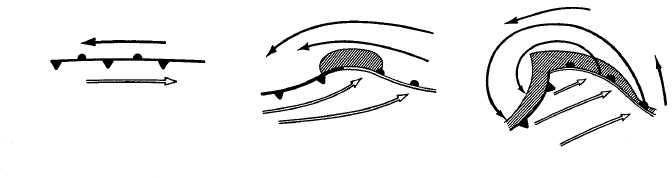

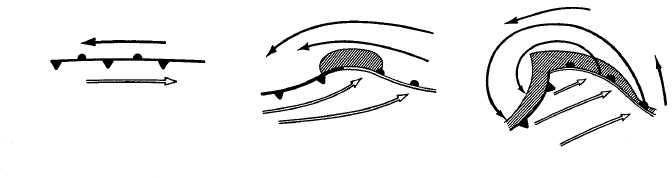

Stable Waves

A stable wave is one that neither develops nor

occludes, but appears to remain in about the same state.

Stable waves usually have small amplitude, weak low

centers, and a fairly regular rate and direction of

movement. The development of a stable wave is shown

in views A, B, and C of figure 4-21. Stable waves do not

go into a growth and occlusion stage.

4-22

COLD

AIR MASS

AG5f0421

POLAR

FRONT

WARM

AIR MASS

A. COLD AND WARM AIR FLOW

B. FORMATION

C. TYPICAL WAVE

Figure 4-21.—Life cycle of a stable wave cyclone.