. The disturbance is decelerating or moving at a

constant speed.

. The system has a northward component of

motion.

. A migratory anticyclone passes to the north of the

storm center.

. A strong net outflow (divergence) is manifested

by anticyclonic flow in the upper levels (200 hPa).

. Long waves are slowly progressive. (Applicable

to genesis also.)

. The trade inversion is absent; convection deep.

Other considerations to bear in mind:

l Intensification occurs when the cyclone passes

under an upper-level trough or cyclone, provided there

is relative motion between the two. There is some

indication that intensification does not take place when

the two remain superimposed.

. Poleward movement of the cyclone is favorable

for intensification; equatorward motion is not favorable.

. Intensification occurs only in areas where the sea

surface temperature is 79°F or greater, with a high

moisture content at all levels.

l Other factors being equal, deepening will occur

more rapidly in higher than in lower latitudes. (Coriolis

force is stronger.)

l When a storm moves overland, the intensity will

immediately diminish.

The expected amount of

decrease in wind speeds can be 30 to 50 percent for

storms with winds of 65 knots or more; and 15 to 30

percent for storms with less than 65 knots. If the terrain

is rough, there is more decrease in each case than if the

terrain is flat.

Once an intense tropical cyclone has formed, there

will be further changes in its intensity and in the course

of its motion within the Tropics and during recurvature.

The forecaster should consider these changes in

connection with the predicted path of movement.

MOVEMENT

Tropical cyclones usually move with a direction and

speed that closely approximates the tropospheric current

that surrounds them. Logically, therefore, charts of the

mean flow of the troposphere should be used as a basis

for predicting the movement of tropical cyclones, but

lack of observations generally precludes this approach.

Generally there is a tendency for tropical cyclones

to follow a curved path away from the Equator;

however, departures from this type of track are frequent

and of great variety,

Tropical cyclones move toward the greatest surface

pressure falls and toward the area where the surface

pressure falls increase fastest with time. Calculation is

necessary for this rule to be used.

Numerous theories have been advanced to explain

the cyclone tracks of the past and to predict those of the

future. Observational data have never been sufficient to

prove or disprove most of them.

Tropical storms move under the influence of both

external and internal forces. The external forces are a

result of air currents that surround a storm and carry it

along. The internal forces appear to produce a tendency

for a northward displacement of the storm (which

probably is proportional to the intensity of the storm), a

westward displacement that decreases as latitude

increases, and aperiodic oscillation about a mean track.

Initial Movement of Intense Cyclones

The movement of cyclones that are undergoing or

have just completed initial intensification (about 24

hours) will be as follows:

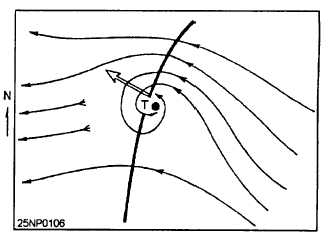

l Storms developing in westward moving wave

troughs in the easterlies move toward the west and also

with a pole ward component given by an angle of

approximately 20° to the right of the axis of the trough

looking downstream. (See fig. 11-1.)

. The motion of storms developing from

preexisting vortices can be extrapolated from the track

of these vortices.

Figure 11-1.-Illustration of initial movement of tropical

cyclones forming in a wave trough In the easterlies.

11-4