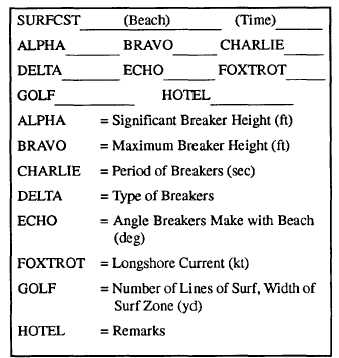

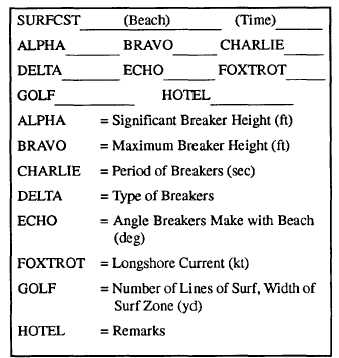

Figure 6-11.-Example of final forecast form.

followed. Most units involved in surface current

forecasts have their own innovations and methods.

CURRENTS

Aerographer’s Mates have a knowledge of the

major ocean currents and the meteorological results of

the interaction of sea and air. Oceanic circulation

(currents) plays a major role in the production and

distribution of weather phenomena. Principal surface

current information such as direction, speed, and

temperature distribution is relatively well known.

Tidal and Nontidal currents

Currents in the sea are generally produced by wind,

tide, differences in density between water masses, sea

level differences, or runoff from the land. They maybe

roughly classed as tidal or nontidal currents. Tidal

currents are usually significant in shallow water only,

where they often become the strong or dominant flow.

Nontidal currents include the permanent currents in the

general circulatory systems of the oceans; geopotential

currents, those associated with density difference in

water masses; and temporary currents, such as

wind-driven currents that are developed from

meteorological conditions. The system of currents in

the oceans of the world keeps the water continually

circulating. The positions shift only slightly with the

seasons except in the Southeast Asia area where

monsoonal effects actually reverse the direction of flow

from summer to winter. Currents appear on most charts

as continuous streams defined by clear boundaries and

with gradually changing directions.

These

presentations usually are smoothed patterns that were

derived from averages of many observations.

Drift

The speed of a current is known as its drift. Drift is

normally measured in knots. The term velocity is often

interchanged with the term speed in dealing with

currents although there is a difference in actual meaning.

Set, the direction that the current acts or proceeds, is

measured according to compass points or degrees.

Observations of currents are made directly by

mechanical devices that record speed and direction, or

indirectly by water density computations, drift bottles,

or visually using slicks and watercolor differences.

Ocean currents are usually strongest near the

surface and sometimes attain considerable speed, such

as 5 knots or more reached by the Florida Current, In

the middle latitudes, however, the strongest surface

currents rarely reach speeds above 2 knots.

Eddies

Eddies, which vary in size from a few miles or more

in diameter to 75 miles or more in diameter, branch from

the major currents. Large eddies are common on both

sides of the Gulf Stream from Cape Hatteras to the

Grand Banks. How long such eddies persist and retain

their characteristics near the surface is not well known,

but large eddies near the Gulf Stream are known to

persist longer than a month. The surface speeds of

currents within these eddies, when first formed, may

reach 2 knots. Smaller eddies have much less

momentum and soon die down or lose their surface

characteristics through wind stirring.

WIND DRIVEN CURRENTS

Wind driven currents are, as the name implies,

currents that are created by the force of the wind exerting

stress on the sea surface. This stress causes the surface

water to move and this movement is transmitted to the

underlying water to a depth that is dependent mainly on

the strength and persistence of the wind. Most ocean

currents are the result of winds that tend to blow in a

given direction over considerable amounts of time.

Likewise, local currents, those peculiar to an area, will

arise when the wind blows in one direction for some

time. In many cases the strength of the wind may be

used as a rule of thumb for determining the speed of the

6-17