You need not place red and blue dots for the entire

chart-only for the area of interest.

Now, to use this advection chart, it should be

compared against the chart from the preceding 12 hours.

From comparison of the red and blue dots, you can

determine if there has been an increase or decrease in

the amount of warm or cold air advection in a particular

area, as well as any change in the intensity of advection.

Then, the advection type and amount, as well as

change, can be applied to determine the possibility of

new pressure system development.

FORECASTING THE MOVEMENT OF

SURFACE PRESSURE SYSTEMS

LEARNING OBJECTIVES Forecast the

movement of surface low- and high-pressure

systems by extrapolation, isallobaric

indications, relation to warm sector isobars,

relation to frontal movement, thickness lines,

relation to the jetstream, and statistical

techniques.

Whether you move the high- or low-pressure areas

first is a matter of choice for the forecaster, Most

forecasters prefer to move the low-pressure areas first,

and then the high-pressure areas.

MOVEMENT OF LOW-PRESSURE

SYSTEMS

Lows determine, to a large extent, the frontal

positions. The y also determine a portion of the isobaric

configuration in highs because gradients readjust

between the two. As a result of knowing the interplay

of energy between the systems, meteorologists have

evolved rules and methods for progging the movement,

formation, intensification, and dissipation of lows.

The general procedure for the extrapolation of

low-pressure areas is outlined below. Although only

movement is covered, the central pressures with

anticipated trends could be added to obtain an intensity

forecast.

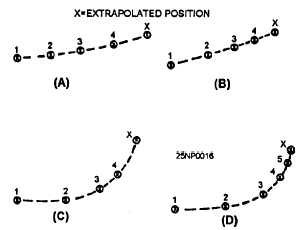

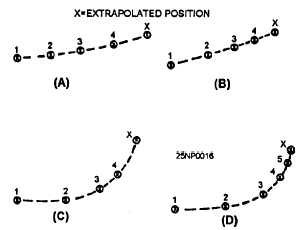

1. Trace in at least four consecutive past positions

of the centers.

2. Place an encircled X over each one of these

positions, and connect them with a dashed line, (See

fig. 3-3.) If you know the speed and direction of

movement, as obtained from past charts, the forecasted

position can be calculated. One word of caution,

straight linear extrapolation is seldom valid beyond 12

hours. Beyond this 12-hour extrapolated position,

deepening/filling, acceleration/deceleration, and

changes in the path must be taken into consideration. It

is extremely important that valid history be followed

from chart to chart, Systems do not normally appear

out of nowhere, nor do they just disappear

3. An adjustment based on a comparison between

the present chart and the preceding chart must be made,

For example, the prolonged path of a cyclone center

must not run into a stationary or quasi-stationary

anticyclone, notably the stationary anticyclones, over

continents in winter. When the projected path points

toward such anticyclones, it will usually be found that

the speed of the cyclone center decreases and the path

curves northward. This path will continue northward

until it becomes parallel to the isobars around the

quasi-stationary high. The speed of the center will be

least where the curvature of the path is greatest. When

the center resumes a more or less straight path, the speed

again increases.

Extrapolation

First and foremost in forecasting the movement

of lows should be their past history. This is a

record of the pressure centers, attendant fronts, their

direction and speed of movement, and their

intensification/weakening. From this past history, you

can draw many valid conclusions as to the future

behavior of the systems and their future motion. This

technique is valid for both highs and lows for short

periods of time.

Figure 3-3.-Example of extrapolation procedure. X is the

extrapolated position.

3-3