time the tropopause is reached. The subtropical highs

are good examples of this type of high. Therefore,

anticyclones found in tropical air are always warm core.

Examples of warm core highs are the Azores or

Bermuda High and the Pacific High.

VERTICAL STRUCTURE OF LOW-PRESSURE

SYSTEMS

Low-pressure systems, like high-pressure systems,

are generally a reflection of systems aloft. They, too,

experience shifts in location and changes in intensity

and shape with height. At times, a surface system may

not be evident aloft and a well-developed system aloft

may not reflect on a surface analysis.

Cold Core Lows

The cold core low contains the coldest air at its

center throughout the troposphere; that is, going

outward in any direction at any level in the troposphere,

warmer air is encountered. The cold core low (figure

3-20)

increases

intensity

with

height.

Relative

minimums in thickness values, called cold pools, are

found in such cyclones. The temperature distribution is

almost symmetrical, and the axis of the low is nearly

vertical. When they do slope vertically, they slope

toward the coldest temperatures aloft. In the cold low,

the lowest temperatures coincide with the lowest

pressures.

The cold low has a more intense circulation aloft

from 850 to 400 millibars than at the surface. Some

cold lows show only slight evidence in the surface

pressure field that an intense circulation exists aloft.

The cyclonic circulation aloft is usually reflected on the

surface in an abnormally low daily mean temperature

often

accompanied

by

instability

and

showery

precipitation. A cold core low is accompanied by a low

warm tropopause. Since the pressure surfaces are close

together, the tropopause is reached at low altitudes

where the temperature is relatively warm. Good

examples of cold core lows are the Aleutian and

Icelandic lows. Occluded cyclones are generally cold

core in their later stages, because polar or arctic air has

closed in on them.

At high latitudes the cold pools and their associated

upper air lows show some tendency for location in the

northern

Pacific

and

Atlantic

Oceans

where,

statistically, they contribute to the formation of the

Aleutian and Icelandic lows.

Warm Core Lows

A warm core low (figure 3-21) decreases intensity

with height and the temperature increases toward the

center on a horizontal plane. The warm low is

frequently stationary, such as the heat low over the

southwestern United States in the summer; this is a

result of strong heating in a region usually insulated

from intrusions of cold air that tend to fill it or cause it

to move. The warm low is also found in its moving form

as a stable wave moving along a frontal surface. There

is no warm low aloft in the troposphere. The tropical

cyclone, however, is believed to be a warm low because

its intensity diminishes with height. Because most

warm lows are shallow, they have little slope. However,

intense warm lows like the heat low over the southwest

United States and hurricanes do slope toward warm air

aloft.

In

general,

the

temperature

field

is

quite

asymmetrical around a warm core cyclone. Usually the

southward moving air in the rear of the depression is

3-19

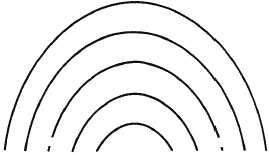

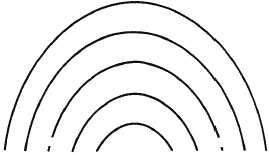

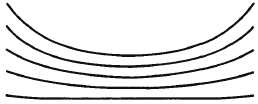

H

H

800MB

800MB

600MB 700MB

900MB 1000MB

1000MB 900MB

700MB 600MB

AG5f0319

Figure 3-19.—Warm core high.

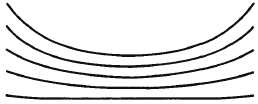

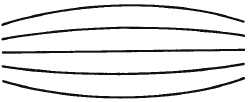

L

L

600MB

600MB

700MB

700MB

800MB

800MB

900MB

900MB

1000MB

1000MB

AG5f0320

Figure 3-20.—Cold core low.

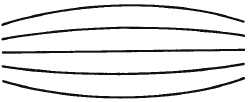

H

L

600MB

600MB

700MB

700MB

800MB

800MB

900MB

900MB

1000MB

1000MB

AG5f0321

Figure 3-21.—Warm core low.