Range Ambiguity

As described earlier, the pulse repetition

frequency largely determines the maximum range of

the radar set. If the period between successive pulses is

too short, an echo from a distant target may return after

the transmitter has emitted another pulse. This would

make it impossible to tell whether the observed pulse is

the echo of the pulse just transmitted or the echo of the

preceding pulse. This produces a situation referred to

as range ambiguity. The radar is unable to distinguish

between pulses, and derives range information that is

ambiguous (unreliable).

In theory, it is best to strike a target with as many

pulses of energy as possible during a given scan. Thus,

the higher the PRF the better. A high PRF improves

resolution and range accuracy by sampling the position

of the target more often. Since PRF can limit maximum

range, a compromise is reached by selectively

increasing the PRF at shorter ranges to obtain the

desired accuracy of measurements.

The maximum unambiguous range (Rmax) is the

longest range to which a transmitted pulse can travel

and return to the radar before the next pulse is

transmitted. In other words, Rmax is the maximum

distance radar energy can travel round trip between

pulses and still produce reliable information. The

relationship between the PRF and Rmax determines

the unambiguous range of the radar. The greater the

PRF (pulses per second), the shorter the maximum

unambiguous range (Rmax) of the radar. The

maximum unambiguous range of any pulse radar can

be computed with the formula: Rmax = c/(2xPRF),

where c equals the speed of light (186,000 miles per

second). Thus, the maximum unambiguous range of a

radar with a PRF of 318 would be 292 miles (254 nmi),

186,000/2 x 318 = 292. The factor of 2 in the formula

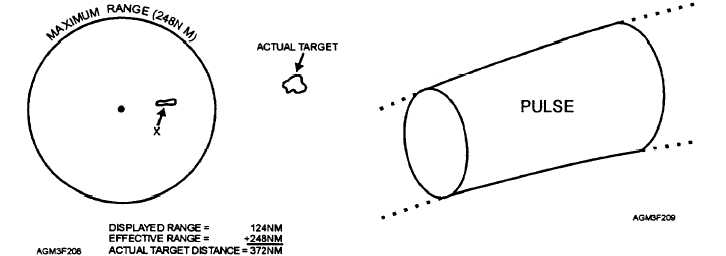

Figure 2-8.—Radar range folding.

accounts for the pulse traveling to the target and then

back to the radar.

Range Folding

While it’s true that only targets within a radar’s

normal range are detected, there are exceptions.

Occasionally, a pulse strikes a target outside of normal

range and returns during the next pulse’s listening time.

This poses a complex problem known as range folding.

Range folding may cause operators to base crucial

decisions on false echoes. The data received from this

stray pulse could be misanalyzed and echoes may be

plotted where nothing exists. The data may look

reliable and the radar may appear to be functioning

properly, adding to the deception of normal operation.

Refer to figure 2-8. Assume a pulse was emitted

during the radar’s previous scan. While it travels

beyond normal range and strikes a target, the radar

emits a second pulse. Since no targets exist within

normal radar range, these pulses will pass each other in

flight. The first pulse now returns while the radar is

expecting the second pulse (during the listening time

of the second pulse). The radar believes that the second

pulse has struck a target 124 nmi from the antenna and

displays. an echo accordingly (target "X"). The

operator is fooled by target "X" and issues a severe

weather warning, when in fact, no clouds are present.

Target "X" was an illusion, a reflection of a

thunderstorm located 372 nmi from the antenna.

Fortunately, the WSR-88D is equipped with a range

unfolding mechanism that attempts to position all

echoes properly.

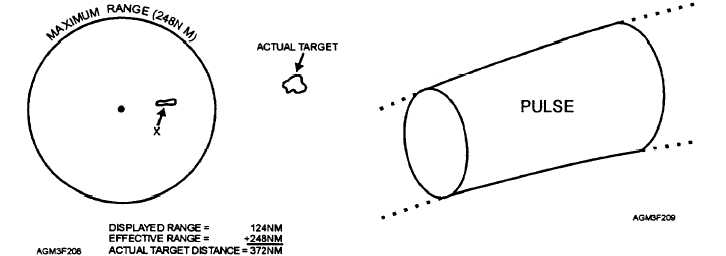

Pulse Volume

As pulses travel they look like a cone with its point

cut off (fig. 2-9). They expand with the beam and

increase in volume. The volume of a pulse is the space

Figure 2-9.—Radar pulse volume. Pulse volume increases with

distance from the antenna as the pulse expands in all

directions.

2-7