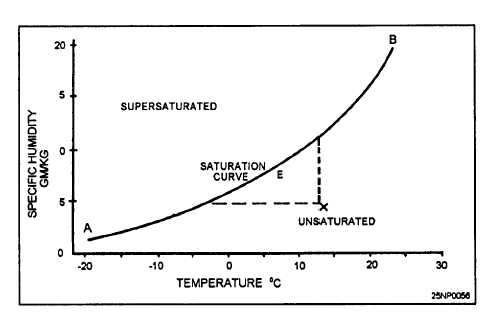

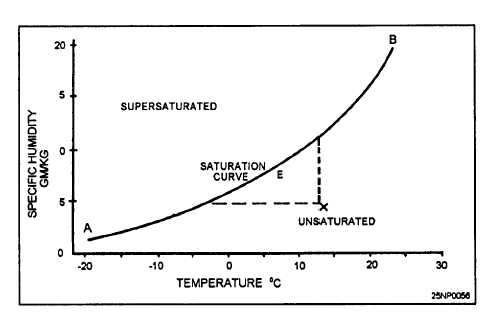

Figure 5-14.-Saturation curve.

An estimate of the formation time of fog, and

possibly stratus, can be aided greatly if some type of

saturation time chart, such as that illustrated in figure

5-17, can be constructed on which the forecasted

temperature versus the forecasted dewpoint can be

plotted. To use this diagram, note the maximum

temperature and consider the general sky condition from

the surface chart, forecasts, or sequence reports, By

projecting the temperature and dewpoint temperature,

an estimated time of fog formation can be forecast. If

smoke is observed in the area, fog will normally form

about 1 hour earlier than the formation line indicates on

the charts because of the abundance of condensation

nuclei.

Air-mass Trajectories

The trajectory of an air mass during the forecast

period can be another important factor in fog formation.

Warm air moving over a colder surface is a primary fog

producer. This can happen when a station is in the warm

sector, following a warm frontal passage. Cooling of

the air mass takes place, allowing condensation and

widespread fog or low stratus to form. To determine the

probabilities of condensation behind a warm front,

compare the temperature ahead of the front with the

dewpoint behind the front. If the temperature ahead of

the warm front is lower than the dewpoint behind the

front, the air mass behind the front will cool to a

temperature near the

causing condensation

stratus.

temperature ahead of the front,

and the formation of fog or low

Over water areas, warm air passing over cold water

may cause enough cooling to allow condensation and

the production of low clouds.

Another instance in which trajectory is important is

when cold air moves over a warmer water surface,

marsh land, or swamp, producing steam fog. In

addition, air passing over a wet surface will evaporate a

portion of the surface moisture, causing an increase in

the dewpoint.

Whenever there is a moisture source

present, air will evaporate a portion of this moisture,

unless the vapor pressure of the air is as great, or greater,

than the vapor pressure of the water. A dewpoint

increase may be enough to allow large eddy currents,

nocturnal cooling, or terrain lifting to complete the

saturation process and allow condensation to occur.

CONDITIONS FAVORABLE FOR GROUND

OR RADIATION FOG

For the formation of ground or radiation fog, ideally,

the air mass should be stable, moist in the lower layers,

dry aloft, and under a cloud cover during the day, with

clear skies at night. Winds should be light, nights long,

and the underlying surface wet.

A stationary, subsiding, high-pressure area

furnishes the best requirements for light winds, clear

skies, stability, and dry air aloft. If the air in the high

has been moving over a body of water, or if it lies over

ground previously moistened by an active precipitating

front, the wet surface will cause an increase in the

dewpoint of the lowest layers of the air. In addition, long

5-21